-

La prima occupazione del sito

5000 – 3900 (VIII)I livelli più antichi attualmente raggiunti dallo scavo archeologico riguardano il periodo Tardo Calcolitico 2, datato alla fine del V millennio a.C.

I livelli in questione sono caratterizzati dal rinvenimento di diversi livelli di occupazione, con carattere essenzialmente domestico. Le case sono caratterizzate dalla presenza di cortili attorno ai quali si sviluppano diversi vani, tra cui, elemento costante, è la presenza di una cucina. Questa si identifica molto chiaramente dalla presenza costante di un forno a cupola, a volte accompagnato da focolari, e dalla presenza di macine e pestelli per la lavorazione dei cereali.

Sono state trovate sui muri in mattoni tracce di intonaci dipinti. I rifacimenti sono continui, come testimoniato da aggiunte e modifiche alle murature.

La ceramica di questi livelli mostra chiari paralleli con gli sviluppi contemporanei delle regioni a sud-ovest (regione di Gaziantep e Amuq).

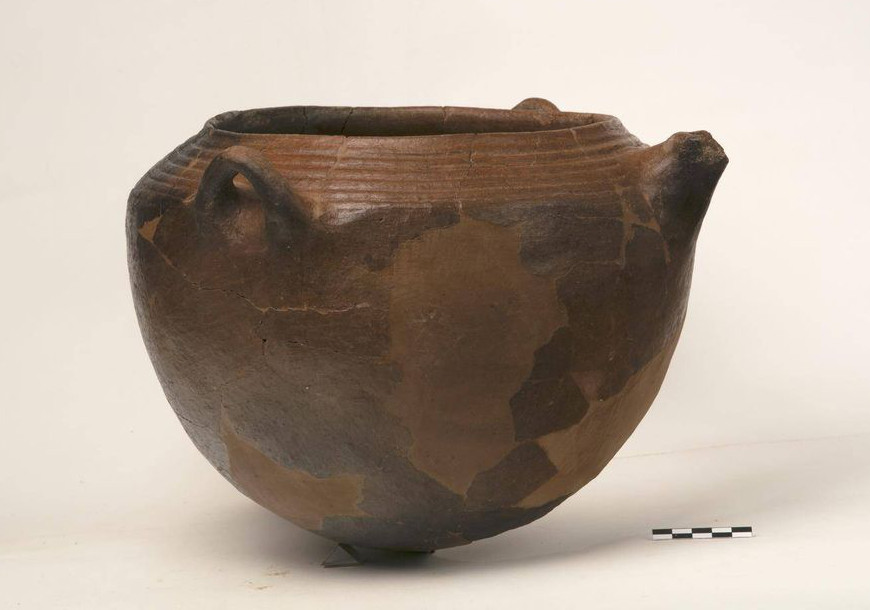

Caratteristica è una ceramica da cucina di colore nero o violaceo, con la superficie esterna interamente sgraffiata. -

L’emergere delle élite e della componente ideologico-religiosa

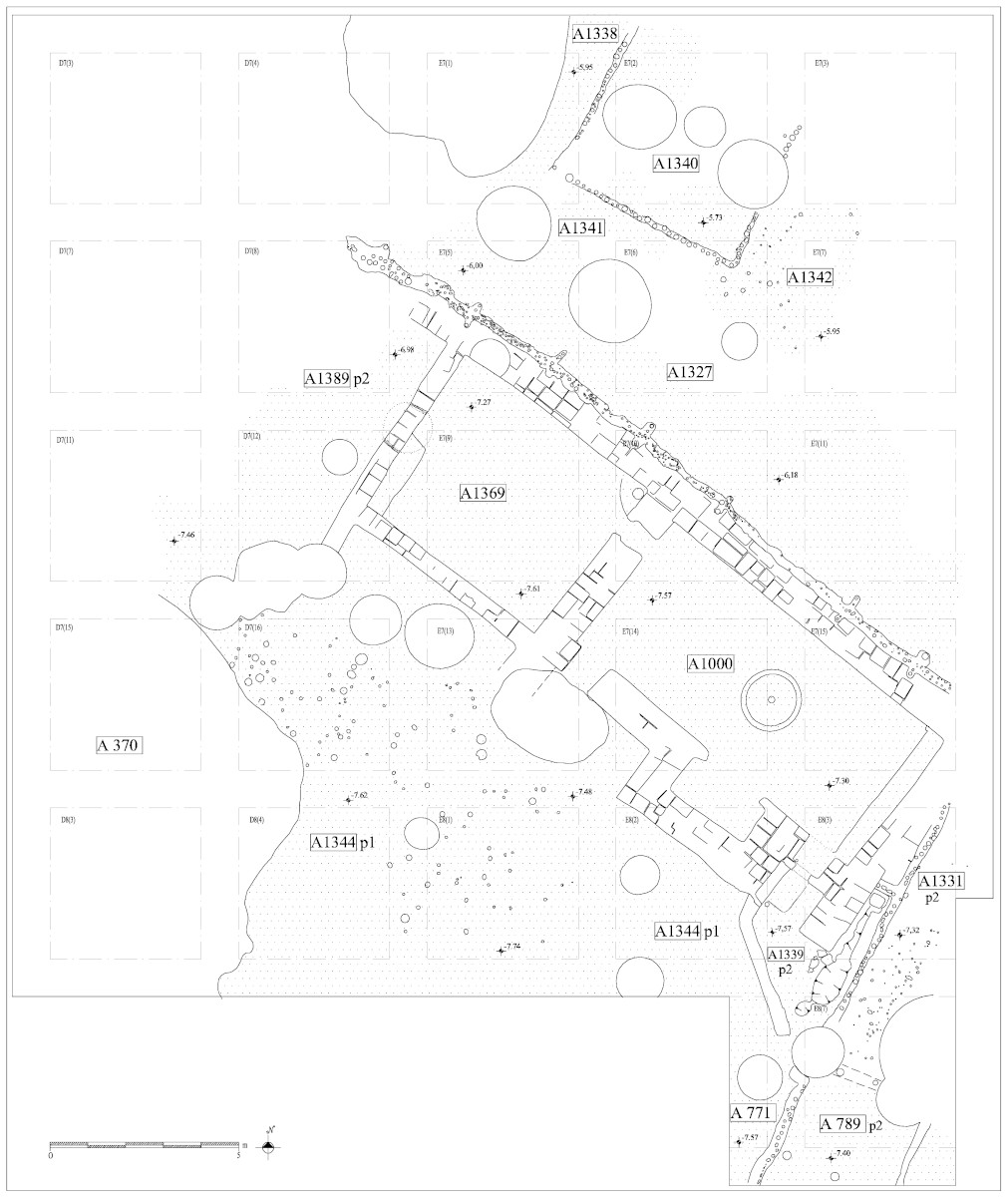

3900 – 3400 (VII)La prima occupazione di Arslantepe risale almeno al VI millennio a.C. ma i più antichi livelli di abitato raggiunti su ampie estensioni si riferiscono al Tardo Calcolitico, periodi VIII (4200-3900 a.C.) e VII (3800-3400 a.C.) della sequenza del sito. Il periodo VII comprende 7 livelli d’abitato, con evidenze archeologiche che testimoniano il ruolo centrale del sito nella regione di Malatya e la sua piena partecipazione alla formazione delle società proto-statali del Vicino Oriente.

Nell’area nord-est della collina si trovano abitazioni in mattoni crudi di una o due stanze, in qualche caso decorate da pitture geometriche in rosso, nero e bianco, aree di lavoro con forni, e sepolture sotto i pavimenti delle case.

Più in alto, sulla sommità del tell erano collocati gli imponenti edifici di rappresentanza con muri in mattoni crudi spessi 1-1,20 m, articolati in complessi diversificati. Nell’area più settentrionale si trovavano aree di lavoro e conservazione ed edifici a carattere “privato”, tra cui un grande edificio con tracce di pitture geometriche in rosso e nero e colonne in mattoni crudi e fango rivestite di intonaco lungo le pareti. Sul pavimento sono stati trovati oggetti simbolici o di prestigio quali una testa di mazza in calcare e un oggetto in ceramica simile agli “idoletti a occhi” di Tepe Gawra e Tell Brak.

A sud di questa struttura e appartenente ad una fase più tarda, si ergeva un grande edificio a pianta tripartita, probabilmente un tempio, che misurava m 22 x 20 e si innalzava su una piattaforma di grandi lastre di pietra e fango, con planimetria mesopotamica, ma un sistema di fondazioni e basamento tutt’oggi unico nel suo genere. I materiali ritrovati all’interno sono locali, come le centinaia di ciotole trovate in questo tempio e negli edifici ad esso connessi, che, a differenza di quelle mesopotamiche, sono fatte al tornio lento. Insieme alle ciotole sono state trovate anche numerose cretule con le impronte di sigillo, indizio che nell’edificio dovevano svolgersi attività di redistribuzione di alimenti in contesto cerimoniale, probabilmente come compenso per attività di lavoro svolte.

Le attività artigianali specializzate, quali la metallurgia e la produzione ceramica in serie, suggeriscono forme complesse di organizzazione del lavoro, anche se non ancora sotto il controllo centrale, come suggerirebbero i numerosi marchi da vasaio riconosciuti.

La cultura Tardo Calcolitica di Arslantepe ha forti somiglianze con quella di altri siti della della Siria nord-occidentale e della pianura dello Amuq. Sono numerosi gli elementi di collegamento con le contemporanee culture dell’alta Mesopotamia, ma le relazioni con le aree meridionali che avevano caratterizzato il precedente periodo di Ubaid non sono così intense. -

L’emergere del Palazzo alla fine del IV millennio a.C.

3400 – 3100 (VI A)Negli ultimi secoli del IV millennio ad Arslantepe è attestato un grandissimo sviluppo di quel sistema di centralizzazione e redistribuzione dei beni già riconoscibile intorno alla metà del IV millennio a.C. nel grande tempio Calcolitico (periodo VII), divenendo anche un sistema di rafforzamento del potere politico centrale e delle élites che lo rappresentavano.

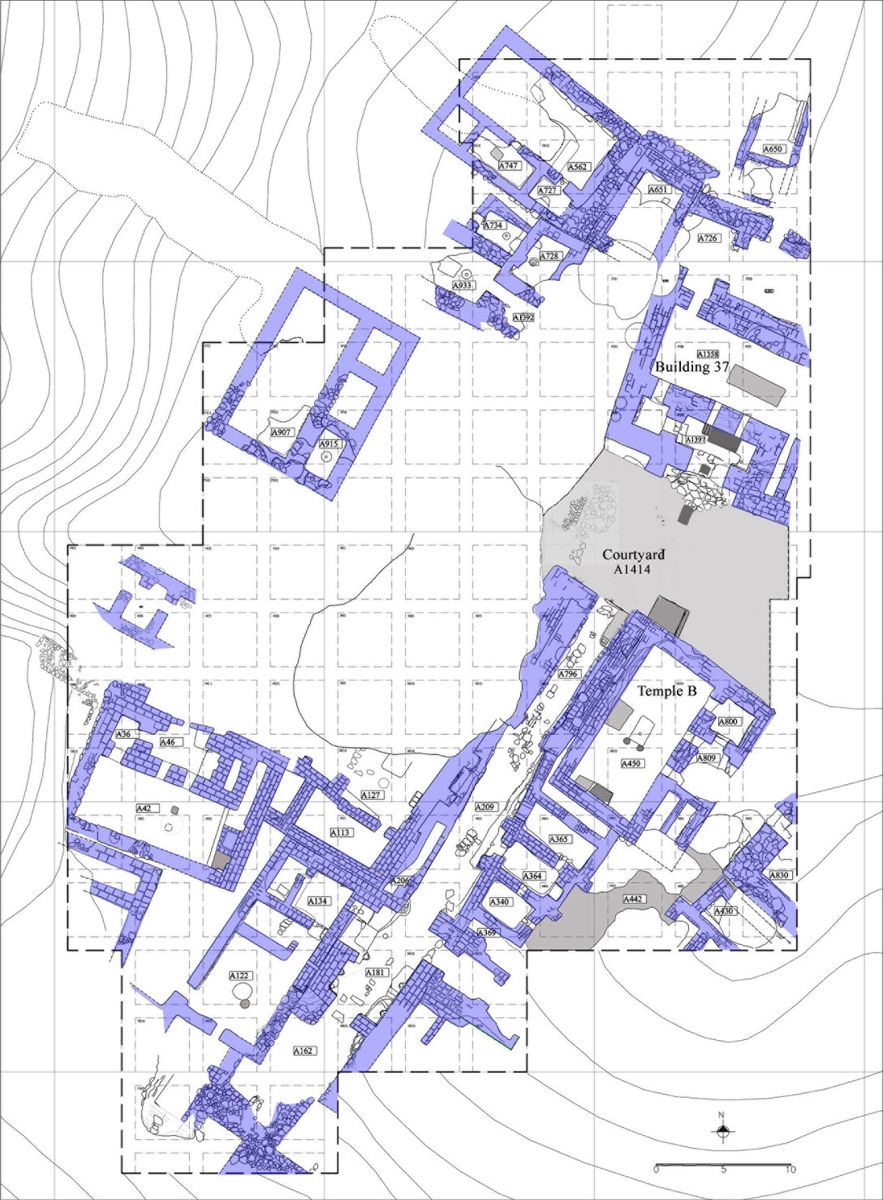

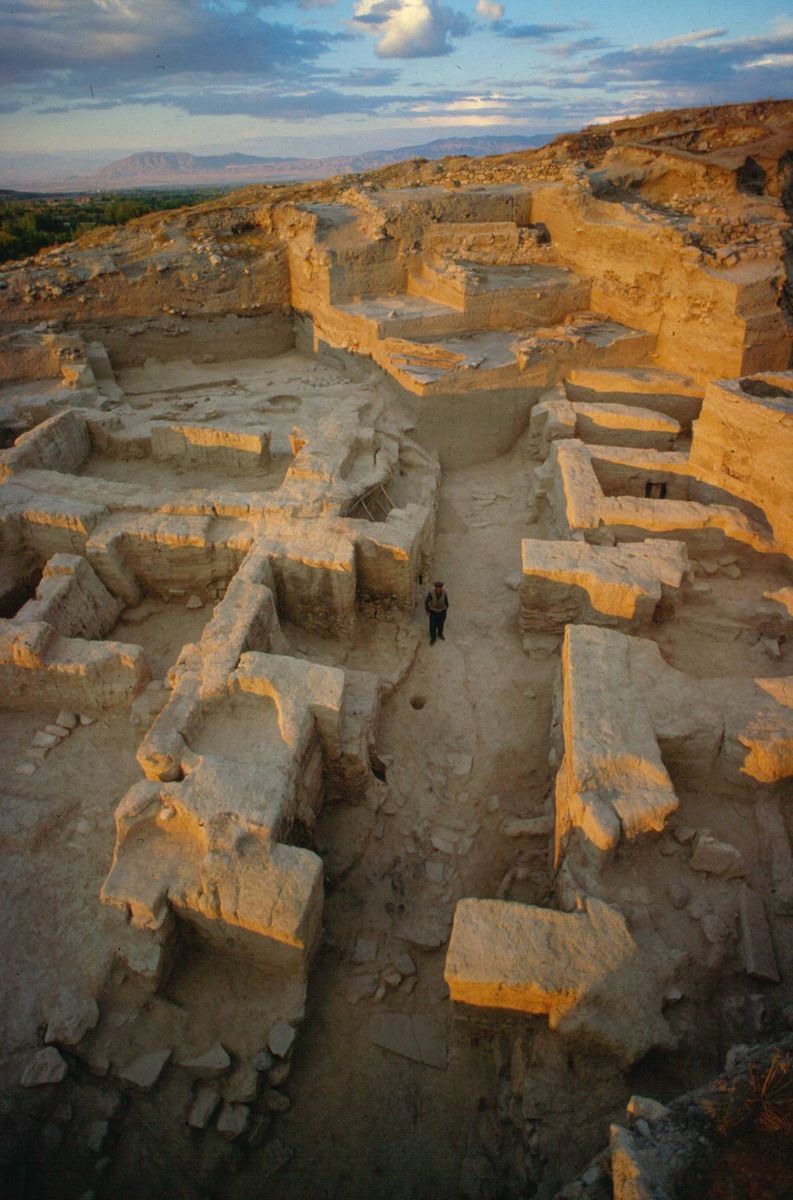

A questo periodo, corrispondente alla fase Tardo Uruk in Mesopotamia, si riferisce la costruzione di un grande complesso architettonico pubblico monumentale, che, per la sua articolazione in settori funzionalmente e architettonicamente differenziati (templi, magazzini, aree di scarico di materiale amministrativo, cortile, corridoi) può essere considerato il primo esempio conosciuto di “palazzo” in tutto il Vicino Oriente con aree pianificate per l’esercizio delle principali funzioni pubbliche, religiose e secolari.

Tutta l’area era dominata da un grosso edificio monumentale di rappresentanza, usato probabilmente per i ricevimenti, nella parte più elevata del pendio della collina antica, e nella parte più alta del palazzo, in fondo ad un lungo corridoio che vi conduceva, direttamente dall’ingresso. Due templi erano anch’essi situati sulle parti più elevate del pendio della collina antica, ma era probabilmente riservato alle elite, mentre l’accesso all’edificio principale doveva essere concesso a tutti. La pianta e le dimensioni dei due templi di Arslantepe sono quasi identiche e mostrano dei caratteri di originalità che fanno sì che queste strutture, pur rientrando genericamente in una tradizione che accomuna tutte le regioni della cosiddetta "Grande Mesopotamia", obbediscano ad esigenze e consuetudini di origine locale.

Al palazzo si entrava attraverso una porta monumentale a camera e un corridoio in netta salita sotto il cui pavimento corre un canale coperto per lo scolo dell’acqua. Ovunque sono evidenti le tracce di un incendio con crolli che hanno conservato in posto tutti i materiali.

Rappresentazioni pittoriche in rosso e nero sul fondo bianco dell’intonaco decoravano i muri del palazzo con scene e motivi complessi che comprendevano figure umane e animali, disposti vicino agli ingressi e lungo le pareti del grande corridoio di accesso.

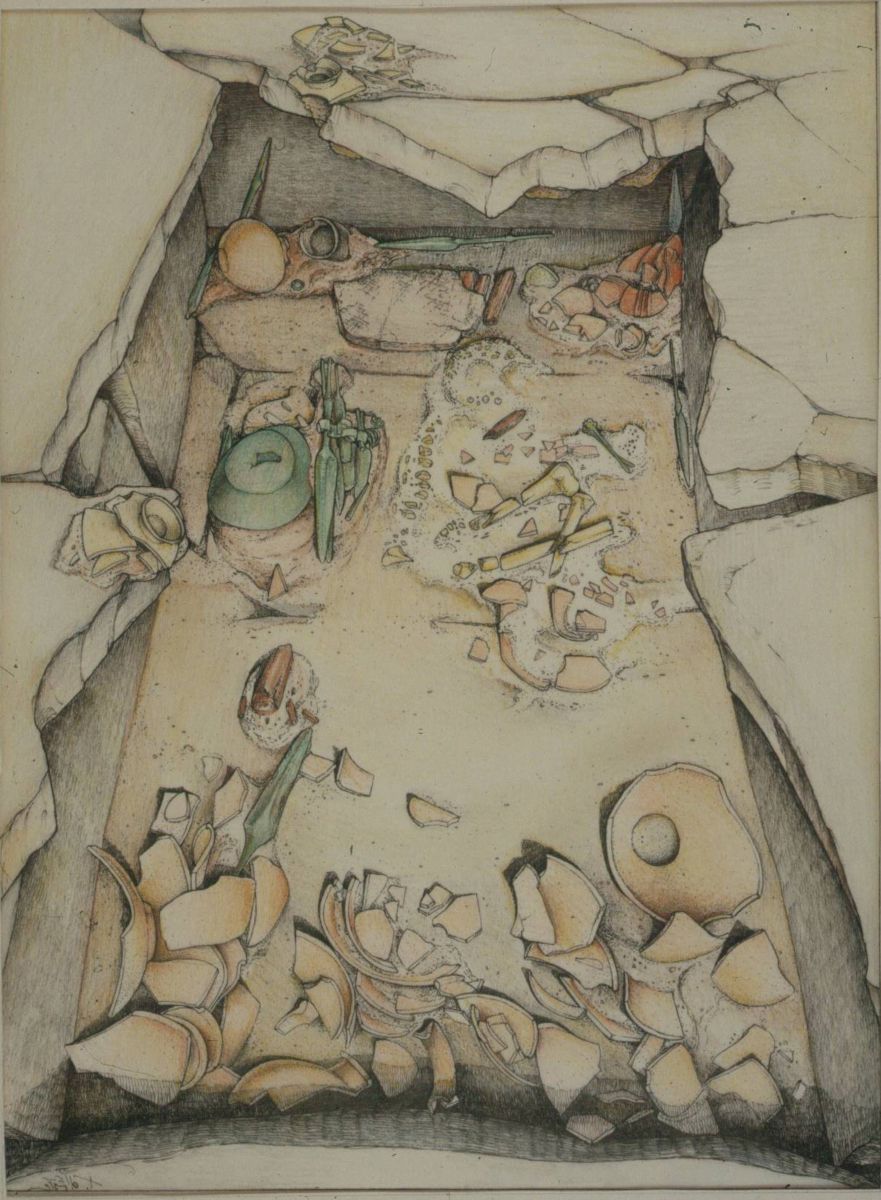

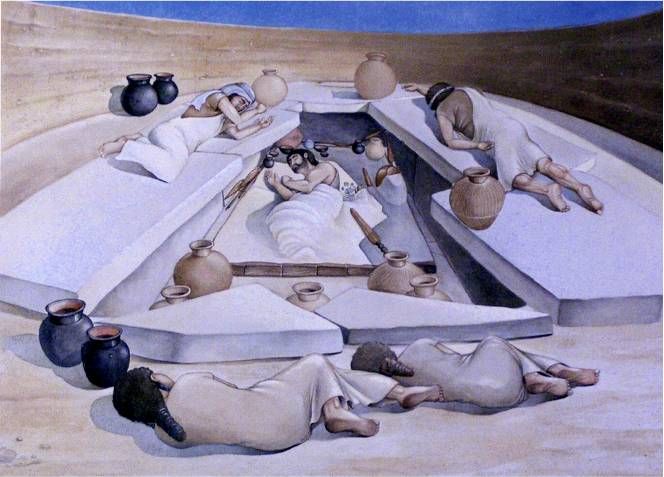

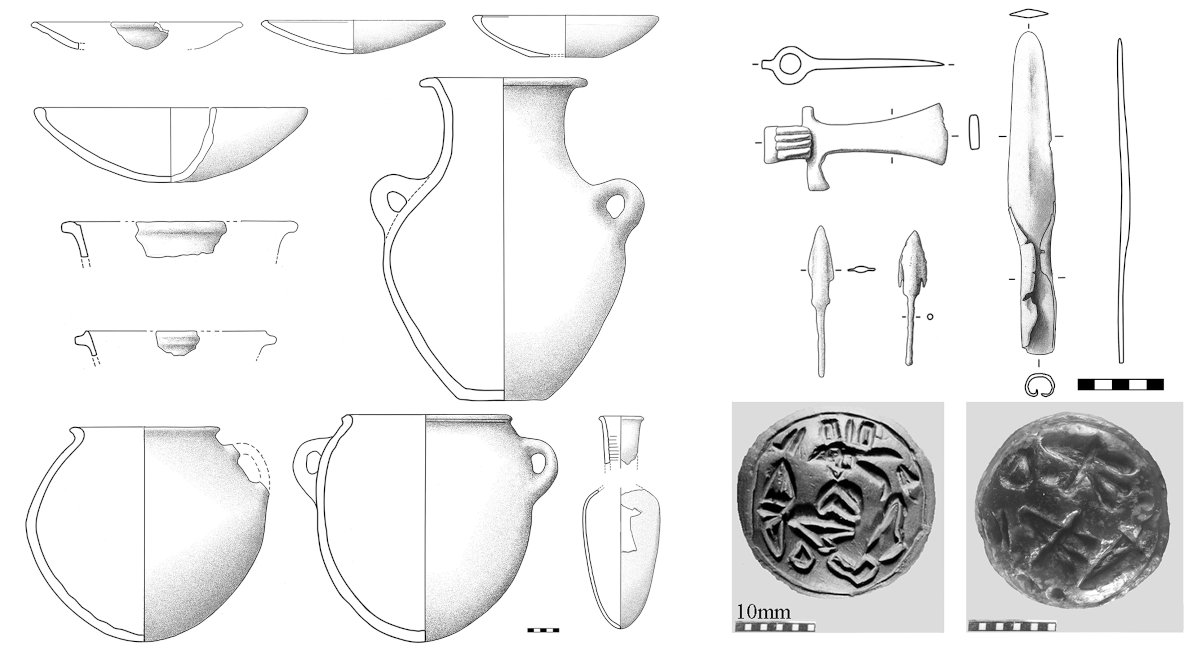

Nella seconda metà del IV millennio si assiste anche ad un grande sviluppo della metallurgia, testimoniato dal ritrovamento di una vasta gamma di oggetti in rame, leghe di rame-arsenico e argento, tra cui spicca un gruppo di 22 armi, spade, lance e una placca a quadrupla spirale, che documentano tra l’altro per la prima volta l’uso della spada al mondo. Anche se i destinatari dei prodotti di questo artigianato dovevano in gran parte essere le élites locali, la produzione intensificata si legava alla capacità del centro di Arslantepe di entrare attivamente nel circuito di circolazione delle materie prime in tutta l’Anatolia Orientale e la Transcaucasia e di fare da intermediario nel commercio con i centri mesopotamici, in un momento in cui la loro richiesta di metallo doveva essere aumentata.

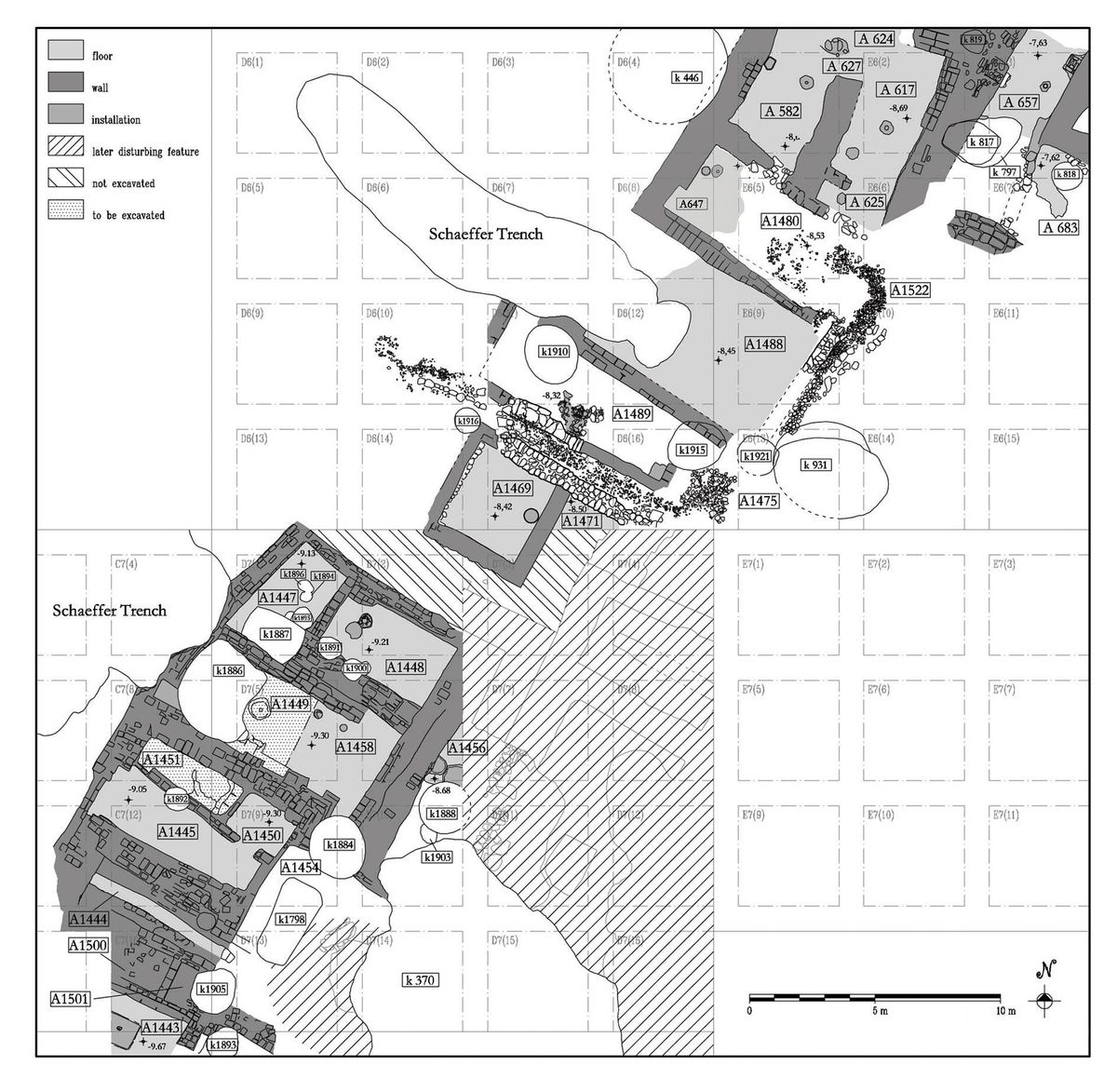

La grande complessità dell’organizzazione amministrativa nel palazzo di Arslantepe è documentata da migliaia di cretule con impressioni di sigillo, rinvenute in vari luoghi del complesso palatino, dove attestano fasi differenti delle attività. Alcune erano in situ in uno dei magazzini del palazzo, altre ammucchiate in luoghi di discarica. In uno stanzino ricavato all’interno del grosso muro del corridoio antistante i magazzini, è stato scoperto un eccezionale deposito di circa duemila cretule che erano state gettate in modo ordinato dopo essere state raccolte per gruppi omogenei recanti lo stesso sigillo e le impronte degli stessi contenitori. Queste cretule costituiscono una sorta di archivio scartato e hanno offerto una straordinaria quantità di informazioni sul sistema amministrativo in uso e sull’arte dell’incisione dei sigilli alla fine del IV millennio.

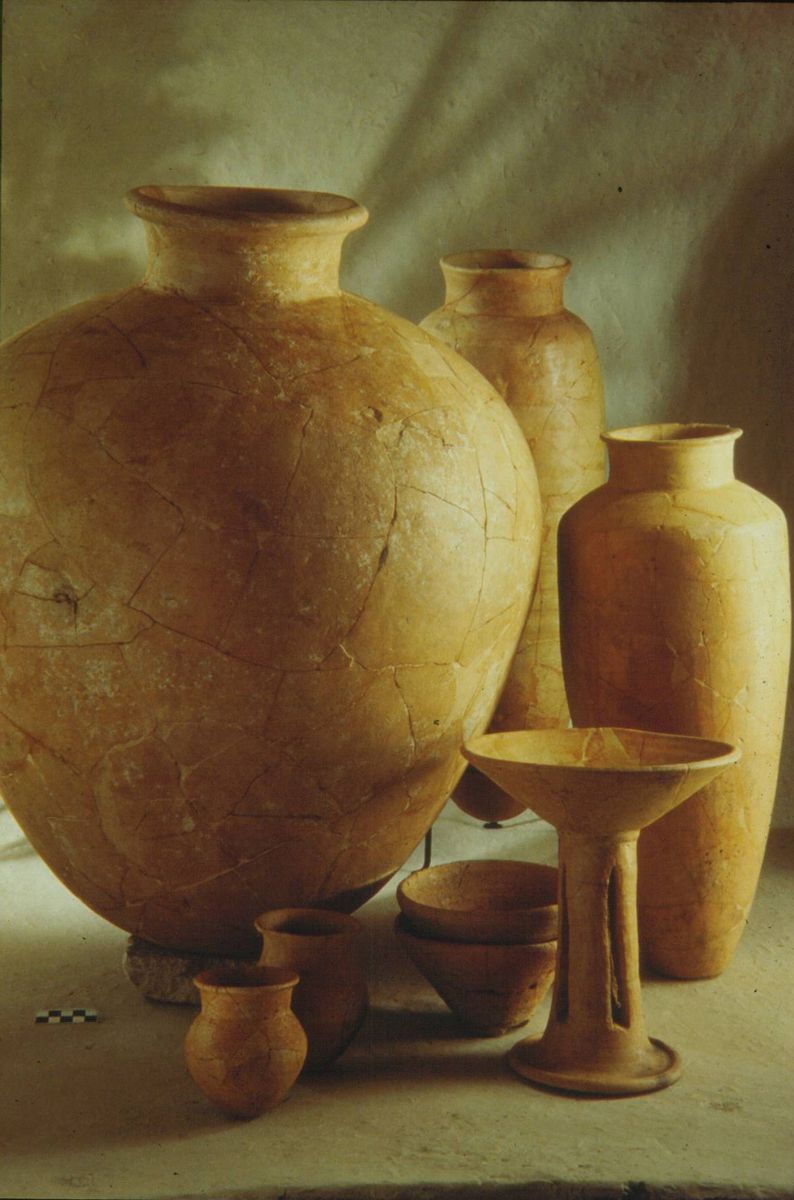

Il settore di immagazzinamento finora messo in luce ha restituito due magazzini, che mostrano le due fasi principali della raccolta e della redistribuzione dei beni: un ambiente era adibito a deposito e conteneva quasi esclusivamente vasi da derrate, grandi contenitori e bottiglie; un’altra stanza, più piccola, probabilmente destinata alla redistribuzione, accanto ad alcuni grandi recipienti, ha restituito centinaia di cretule e di ciotole prodotte in massa. In questa stanza dovevano frequentemente svolgersi, sotto il controllo di funzionari, operazioni di prelievo con apertura e chiusura dei contenitori mediante l’apposizione del sigillo e distribuzione di alimenti, utilizzando le ciotole come contenitori di misura definita.

Attività di raccolta di beni alimentari e redistribuzione dovevano avvenire anche nei due templi del palazzo, come suggeriscono i numerosi vasi trovati in posto nelle stanze laterali, nel caso del Tempio A, e nella sala principale, nel caso del Tempio B, oltre ad un certo numero di cretule. Gli elementi architettonici interni di questi edifici (altari, vaschette, podi) e la presenza vicino agli altari di coppe su piede traforato (le cosiddette “fruttiere”), insieme alla dislocazione dei vasi e al numero ridotto di cretule, indicano che qui tali attività dovevano essere rivestite di un carattere cerimoniale. -

Crisi e instabilità

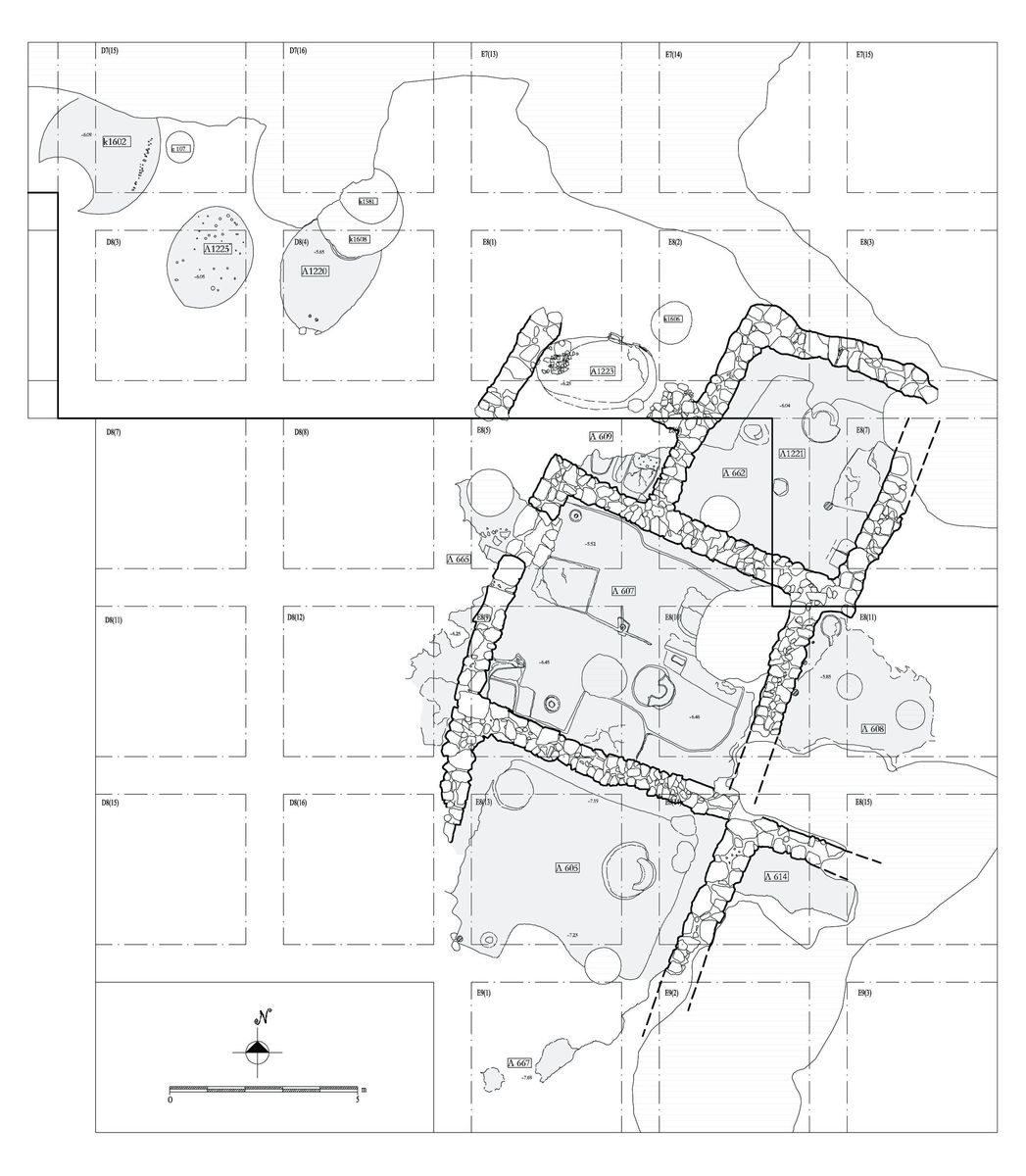

3100 – 3000 (VI B1)Ad Arslantepe la tradizione protourbana si interruppe intorno al 3200 a.C. (periodo VI B1); il crollo degli edifici pubblici della fine del IV millennio fu ricoperto con strati di fango pulito. Nella vasta area così ricavata furono innalzate capanne quadrangolari con gli angoli arrotondati e costituite da un solo ambiente; il pavimento era solitamente ad un livello leggermente inferiore del piano di calpestio, ricoperto da uno strato di intonaco di fango. L’intelaiatura dei muri era composta da file di pali diseguali inseriti in canalette e le pareti formate da canne rivestite d’argilla.

Nella parte più alta del tepe vi era però una capanna più grande di altre, divisa al suo interno in tre parti e isolata dal resto del sito da un lungo e spesso muro in legno e fango. Inoltre, nello spazio esterno alla capanna sono state rinvenute grosse quantità di ossa che fanno pensare a resti di pasto. Tutto ciò ha portato a ipotizzare che questa potesse essere la capanna di un capo.

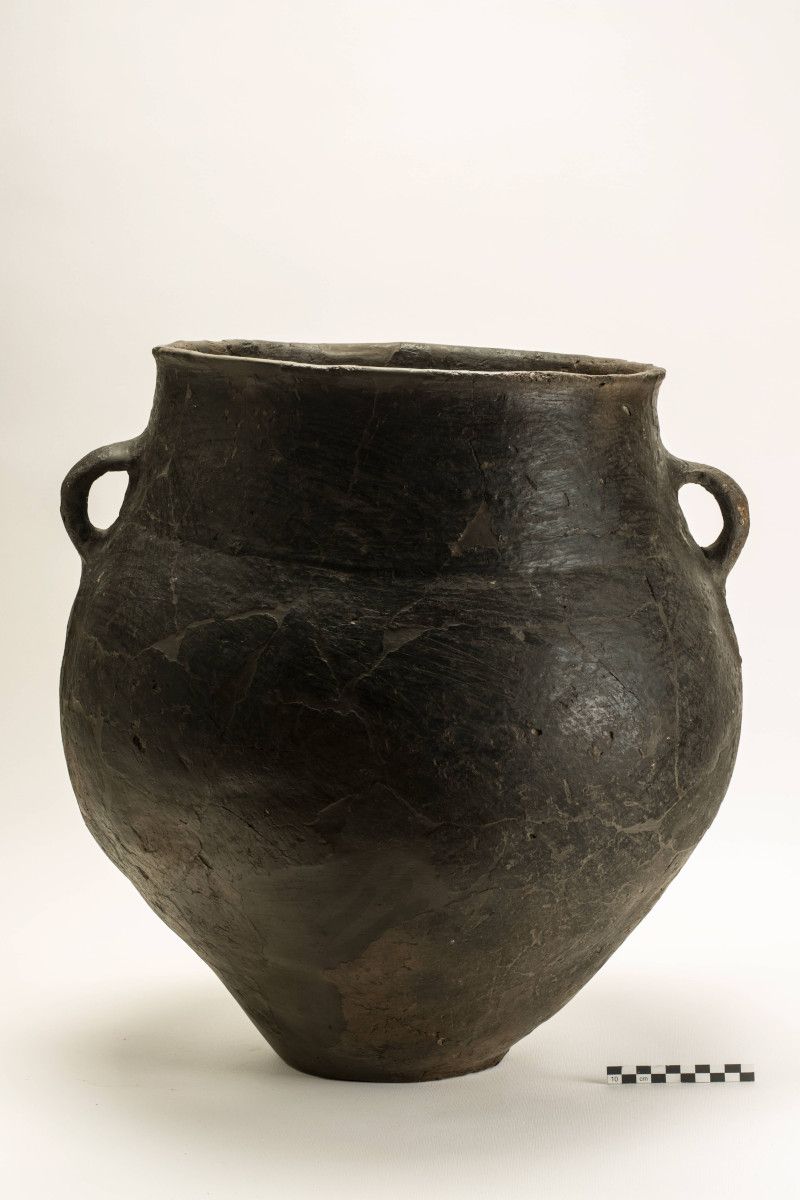

Un’altra struttura particolare si trova invece dall’altro lato del grosso muro. Si tratta di una struttura in mattoni crudi, di architettura quindi diversa da quella delle case ma simile a quella abitualmente utilizzata nel sito. La struttura ha una grossa sala centrale con focolare largo più di 1 metro, attorno al quale probabilmente la gente sedeva quando si incontrava li. Una seconda stanza era piena di vasellame da immagazzinamento; sono stati ricostruiti più di 40 vasi interi che si trovavano stipati nella stanza. Questo edificio doveva avere un carattere comunitario, forse come luogo di immagazzinamento collettivo e di riunione. Il villaggio fu definitivamente distrutto da un incendio che determinò la formazione di uno spesso strato di resti carbonizzati associati a residui di legno riconoscibili anche nelle aree esterne alle strutture domestiche. La presenza di tali resti fa supporre l’esistenza di tettoie e recinti nelle aree aperte, per il ricovero degli animali domestici e per lo svolgimento delle attività quotidiane.

In questo periodo nel sito si assiste ad un cambiamento radicale nella cultura materiale, con ceramiche che sottolineano i forti contatti che la comunità doveva avere con il caucaso meridionale. Molto evidente è la somiglianza delle ceramiche con quelle cosidette “transcaucasiche”. Anche la produzione metallurgica, spesso legata a questi mondi settentrionali, è attestata nel sito. -

Dal villaggio di pastori ad una nuova esperienza urbana

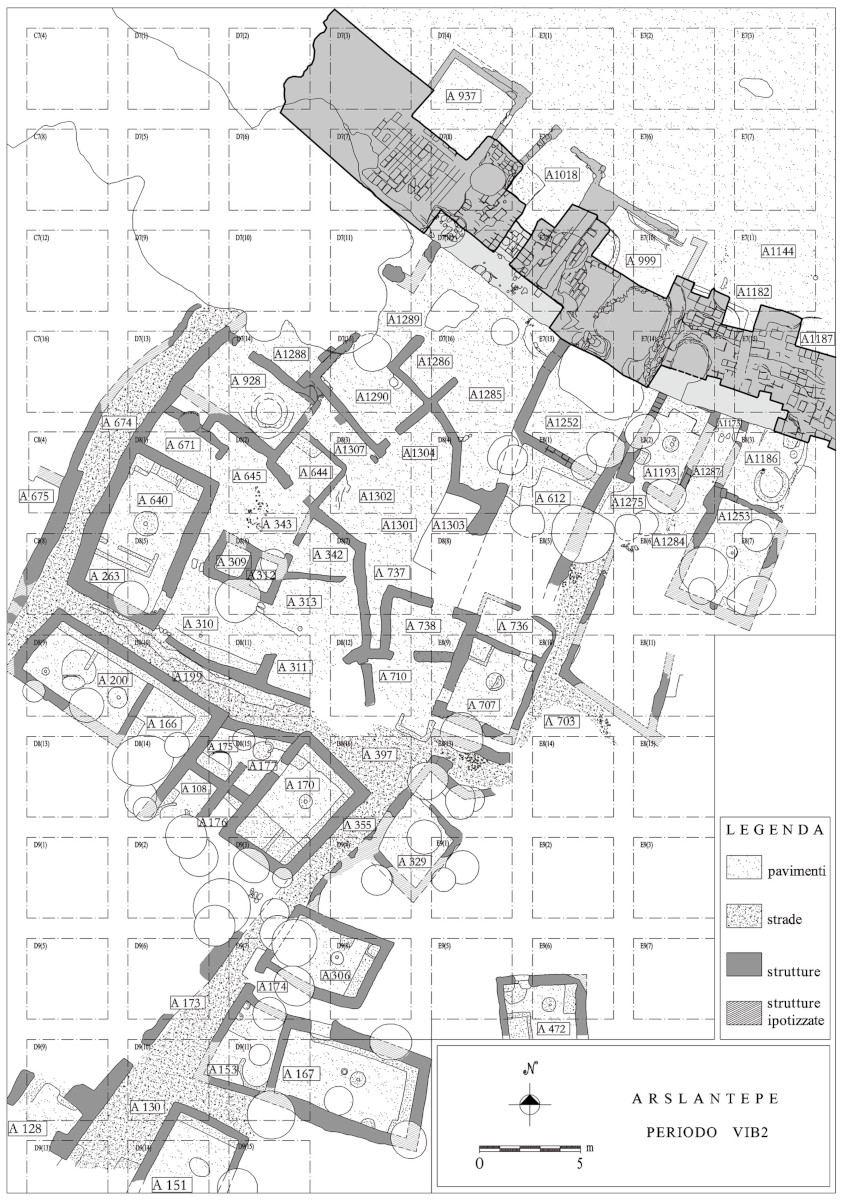

3000 – 2750 (VI B2)Nell’ultima fase del Bronzo Antico I (periodo VI B2) in seguito al definitivo abbandono del villaggio di pastori con cultura trans-caucasica (VI B1), fu costruito un abitato con case in mattoni crudi, di piccole dimensioni separate da strade e cortili destinati a varie attività (macellazione di animali, attività metallurgica di fusione dei minerali di rame). Le strutture domestiche erano costituite da due o tre vani e molto simili tra loro; i vani erano forniti di diverse installazioni come le panchine, che correvano a ridosso delle pareti, le piattaforme, le vaschette o piccole fosse intonacate contenenti macine e macinelli per la lavorazione dei cereali. Al centro delle stanza era presente un focolare circolare con piccola cavità centrale appositamente creata per contenere la brace.

L’abitato venne distrutto da un violento incendio e i pavimenti delle case e degli spazi esterni furono quasi interamente coperti da cereali carbonizzati, forse i resti di un intero raccolto che in origine doveva essere collocato sui solai lignei. Oltre al grano e all’orzo sono stati trovati vinaccioli di vite domestica. Il villaggio sorgeva sul pendio della collina antica ai piedi ad una sorta di cittadella o acropoli, circondata da un grande muro di cinta 5 m di spessore con fondazioni in pietra e alzato in mattoni crudi. L’assetto del villaggio del VI B2 rivela come l’organizzazione politica dell’abitato fosse completamente diversa da quella del sistema palatino precedente basato sul controllo economico della comunità. Nonostante l’intermezzo costituito dall’arrivo su tell di gruppi pastorali di origine trans caucasica, si nota una forte continuità di tradizioni nelle produzioni ceramiche e nella cultura materiale, che, ancora per un breve lasso di tempo, mantengono in vita le tradizioni della fase del palazzo. In questo periodo, infatti, il ruolo della ceramica rosso-nera si riduce, mentre ricompare la ceramica tornita che sembra aver accolto ora tutti i modelli della cultura Tardo Uruk, evoluti in un repertorio locale caratteristico delle culture del Bronzo Antico I in tutta la valle dell’Alto Eufrate. Il periodo VI B2 ad Arslantepe rappresenta l’ultima fase di significativi rapporti tra la regione di Malatya e l’ambiente siro-mesopotamico. I legami tra le regioni a nord e a sud del Tauro si affievolirono notevolmente dopo la fine di questo periodo e la catena montuosa divenne una vera barriera non solo geografica ma anche politica e culturale. -

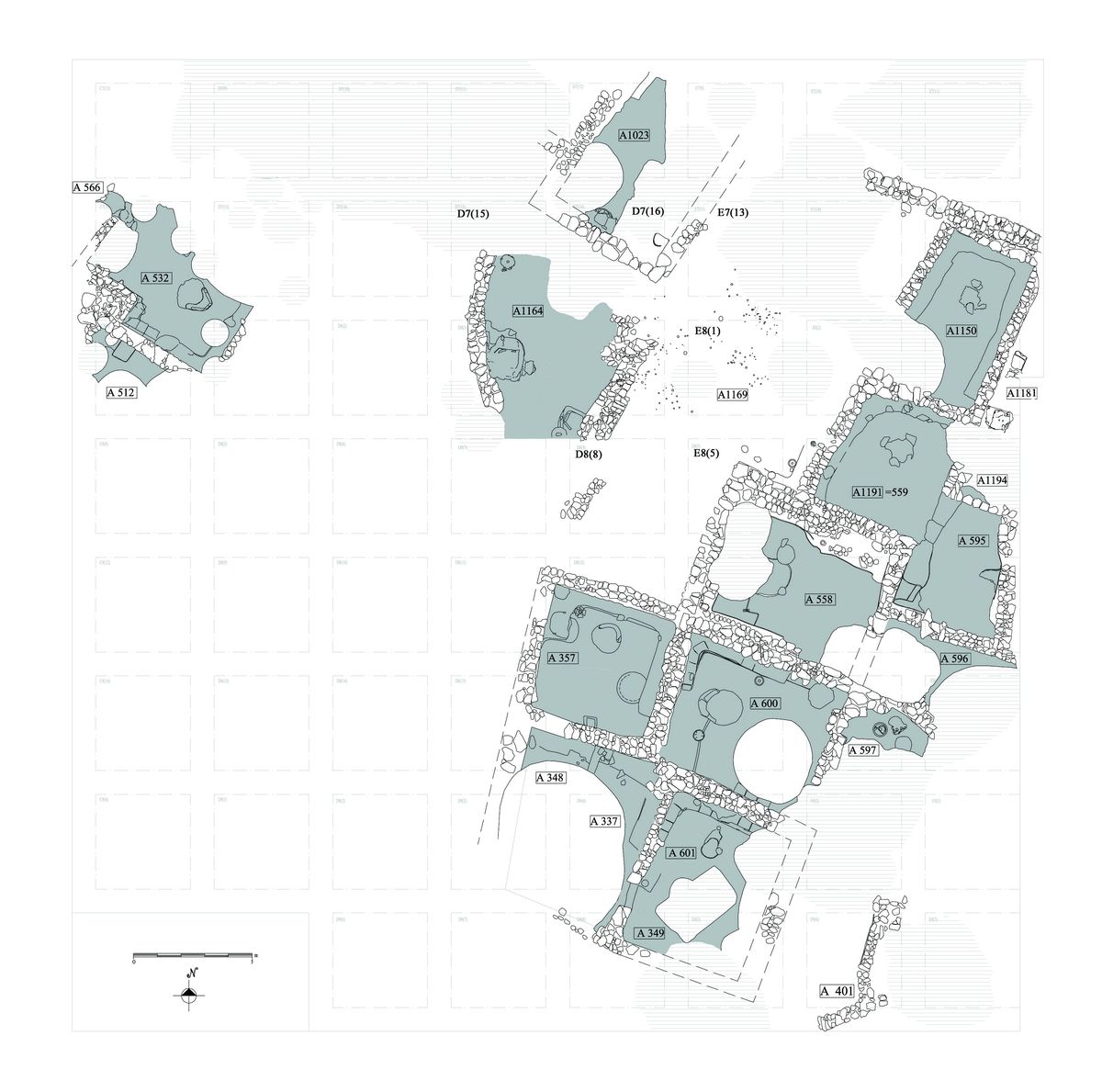

Influenze orientali

2750 – 2500 (VI C)L’influenza del caucaso meridionale contribuì a modificare profondamente gli assetti organizzativi e la cultura delle comunità dell’Alto Eufrate nei successivi sviluppi dell’Antica Età del Bronzo. Si formarono dei nuclei regionali molto più circoscritti e si interruppero i tradizionali rapporti con il mondo siro-mesopotamico, mentre la struttura interna delle comunità appariva decisamente più semplice e meno stratificata.

Il periodo VI C (2750-2500 a.C.) rappresenta l’inizio di una nuova fase culturale ad Arslantepe. L’abitato si restringe notevolmente e il settore sud-ovest della collina è utilizzato come area marginale all’abitato ed è caratterizzata dalla presenza di numerosi pozzi e di fosse circolari rivestite di fango. Tali pozzetti sono scavati per la conservazione del cibo e per lo scarto dei rifiuti. In rari casi sono state messe in luce fosse, identiche in tutto a quelle precedentemente descritte, contenenti resti umani nella maggioro case dei casi disarticolati o incompleti, privi di corredo o talvolta associate ad ossa animali, tra cui è da segnalare lo scheletro intero di un cane.

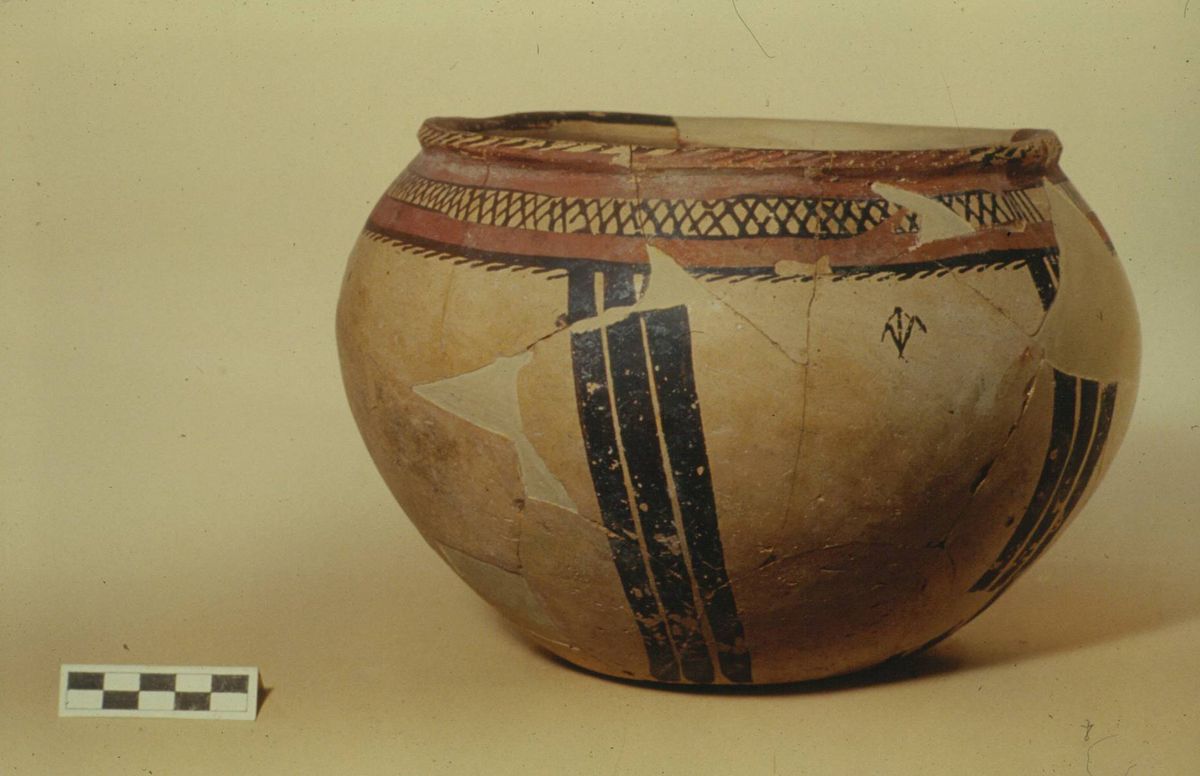

La parte alta del tell è occupata da un complesso di abitazioni costituite da grandi stanze quadrangolari e con fondamenta di pietra, sulle quali insisteranno se strutture domestiche della fase successiva. La suddivisione degli spazi interni e le attrezzature domestiche cambiano notevolmente rispetto al periodo precedente: compaiono un nuovo tipo di forno a volta e focolari con spalliera a ferro di cavallo, che, sostituendo i semplici focolari circolari a fossetta centrale dei periodi precedenti, costituiscono una caratteristica delle culture anatoliche settentrionali. Dagli scavi è emerso, attraverso l’analisi architettonica e della cultura materiale, quanto l’occupazione del Bronzo Antico II fosse diversa rispetto alle fasi precedenti. Per quanto riguarda la cultura materiale si nota la scompare della ceramica prodotta al tornio, al suo posto subentra un nuovo tipo di produzione che è quella della ceramica dipinta che contemporaneamente, seppur con stili differenti, sembra svilupparsi anche tanto nell’area di Malatya, quanto in quella di Elazig e del Keban, dove si osservano cambiamenti culturali paralleli. La ceramica rosso-nera appare come un’evoluzione locale della produzione transcaucasica. I gruppi che occuparono la piana di Malatya in questo periodo avevano una certa mobilità, come è indicato dal ritrovamento di un piccolo sito stagionale di pastori sulle colline rocciose del Gelinciktepe, di fronte ad Arslantepe. -

Verso una nuova città fortificata

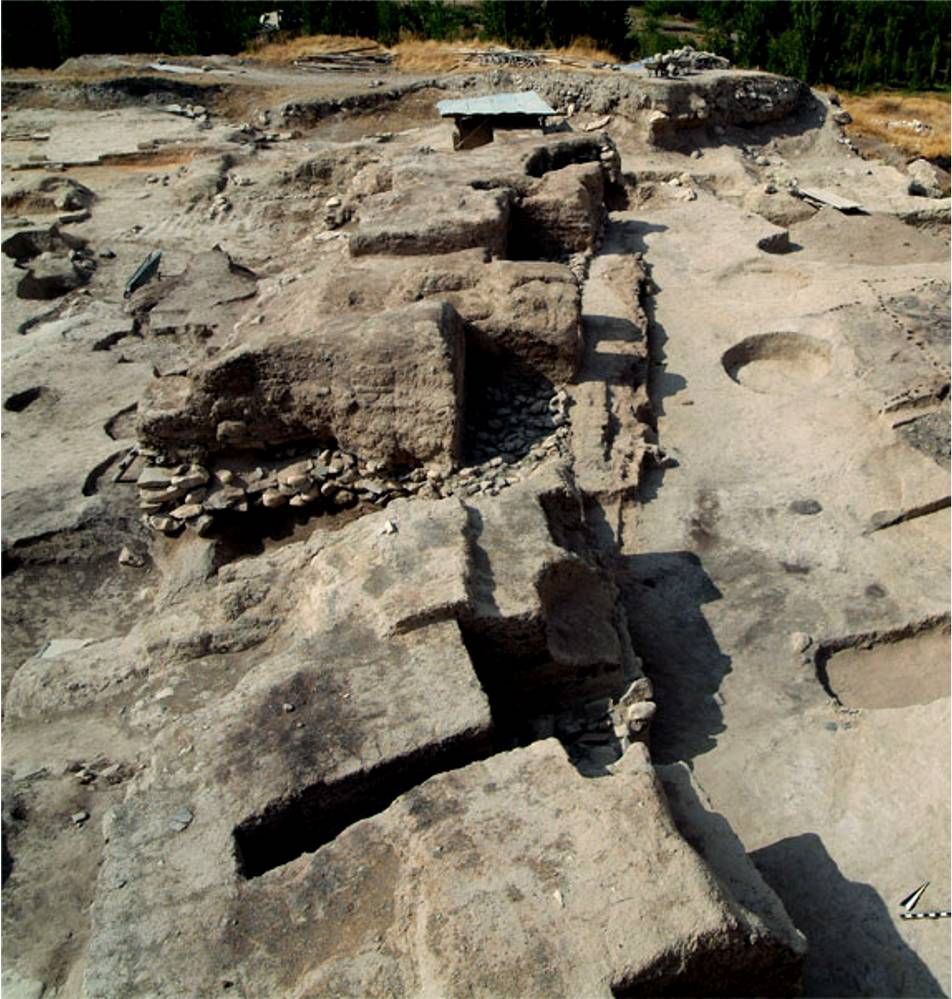

2500 – 2000 (VI D)A partire dalla metà del III millennio a.C. il pendio viene gradualmente rioccupato. Il nuovo abitato, che mostra una precisa pianificazione urbanistica, si imposta su una terrazzata ed è caratterizzato da strutture quadrangolari di grandi dimensioni separate da vie, piazze e canali. La forma delle case, le installazioni e le tecniche costruttive trovano confronti in altri siti dell’Anatolia nord-orientale e rimarranno invariati fino alla fine del millennio. Oltre a queste vi sono anche diversi di edifici ovali, parzialmente interrati, il cui uso è difficile da ricostruire a causa dell’assenza degli elementi di arredo e delle installazioni più comuni. Gli scavi hanno messo in luce, al margine dell’abitato, un possente muro di cinta in mattoni crudi su basamento in pietra con bastione semicircolare che attesta per la prima volta la costruzione di una vera e propria fortificazione urbana, presente dei siti di questo periodo in tutta la regione.

La presenza della cinta muraria indica un aumento della conflittualità, forse legato alla competizione tra insediamenti autonomi. Il modello insediativo tipico dell’area è caratterizzato da cittadelle fortificate, che suggeriscono una crescita demografica a cui non si accompagna però la formazione di strutture politiche territoriali complesse. Nonostante Arslantepe durante il Bronzo Antico III fosse ancora il centro più grande dell’intera area di Malatya e il fulcro economico e politico della regione, le caratteristiche interne dell’abitato (privo di veri e propri luoghi pubblici preminenti) e l’organizzazione delle produzioni artigianali, sottolineano come esso fosse incentrato su un sistema socio-economico relativamente semplice, anche se basato sull’attività di specialisti.

La ceramica fatta a mano mostra una forte continuità con il periodo precedente con le sue due classi, continuano infatti ad essere prodotte la sia la ceramica rosso-nera sia quella dipinta. Rispetto al Bronzo Antico II però i modelli divengono più standardizzati e la produzione più raffinata. In particolare il vasellame dipinto è di sofisticata fattura e presenta motivi complessi e codificati che dovevano essere eseguiti sicuramente da specialisti, i cui prodotti circolavano ampiamente, anche se nelle sole regioni di Malatya ed Elazig. Unico indizio di contatti più a largo raggio sono rari esemplari di ceramica grigia tornita di origine siriana ad Arslantepe e la presenza di altrettanto rari esemplari di ceramica dipinta di tipo Arslantepe in Anatolia centrale.La metallurgia è ancora sviluppata, come indica il ritrovamento di una bottega di fonditore con numerosi crogioli e forme di fusione, ma anche in questo caso il circuito di circolazione sembra più limitato che in passato. -

Il Medio Bronzo ad Arslantepe

2000 – 1750 (V A)La maggior parte delle testimonianze relative a questo periodo sono state messe in luce nell’area sud-occidentale della collina. Le strutture architettoniche rinvenute sino ad ora sono in condizioni frammentarie e non è possibile per il momento definire con chiarezza la forma e l’estensione dell’abitato, anche perché la complessa stratigrafia di questa fase è stata fortemente disturbata da decine tra fosse e pozzetti. Nel periodo V A si distinguono due fasi, V A1 e V A2, corrispondenti al Bronzo Medio I e II. Nella fase più antica sono state riconosciute numerose aree aperte pavimentate, tagliate da pozzetti riempiti di argilla depurata che potrebbe essere stata destinata ad alcune specifiche lavorazioni artigianali. Alla fase più recente appartiene invece una grande struttura domestica a pianta quadrangolare al cui centro era stato costruito un monumentale focolare a doppio ferro di cavallo. La distruzione di questa struttura ad opera di un incendio è stata probabilmente anche la causa della morte di una donna il cui scheletro è stato rinvenuto nei pressi del focolare. Nella casa si trovavano numerosi vasi di grandi dimensioni destinati a contenere alimenti e liquidi cui si aggiungono numerosi pesi da telaio in pietra ed in argilla che facevano parte dell’attrezzatura di un telaio per la tessitura. Durante il Bronzo Medio l’insediamento di Arslantepe era difeso da un sistema di mura a casematte, che rappresenta una tipica tecnica costruttiva centro-anatolica. Tale sistema di fortificazione era composta da una serie di piccole camere con muri massicci che, sebbene portato alla luce solo in piccola parte, doveva correre lungo tutto il margine della collina.

Durante il Bronzo Medio compaiono nel Vicino Oriente nuove entità politiche, come l’antico regno assiro, che basavano parte del loro potere economico sul controllo delle vie di scambio e sulla fondazione di veri e propri avamposti commerciali nel cuore dell’Anatolia, di cui la colonia di Kültepe-Kanesh è l’esempio più noto. È probabile che anche le regioni di Malatya e di Elaziğ, grazie alla vicinanza dei depositi minerari dell’Antitauro (Ergani Maden), fossero direttamente coinvolte in questa stessa rete commerciale. -

Arslantepe all’inizio del Tardo Bronzo

1700–1400 (V B)Il Periodo VB segna l’intensificarsi dei rapporti con l’Anatolia centrale a seguito sia della continuazione delle relazioni che il sito aveva iniziato a stabilire con questi territori durante il Bronzo Medio sia delle campagne militari intraprese dai sovrani ittiti.

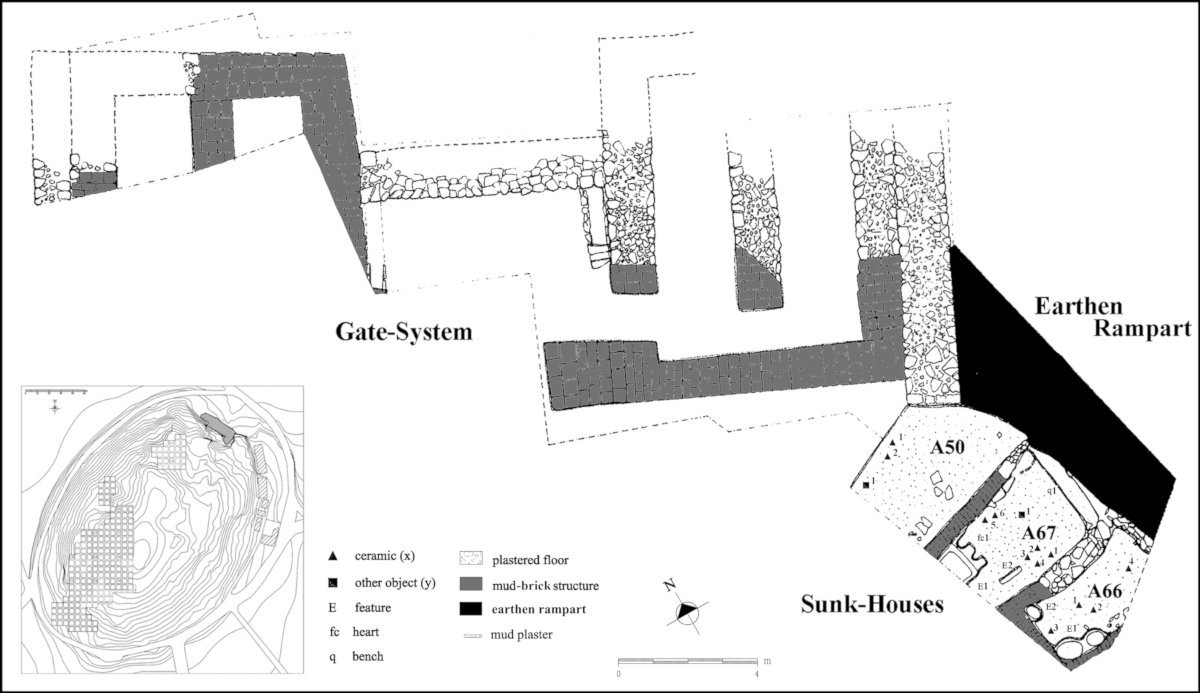

In questo periodo l’intera collina venne cinta da un imponente sistema di fortificazione realizzato con terra pressata e che è stato messo in luce in più punti lungo le pendici del tell. Il terrapieno, che doveva verosimilmente migliorare la difendibilità dell’insediamento ed esser dunque provvisto sulla sua sommità di un vero e proprio muraglione in mattoni, era associato ad una porta urbica che è stata interamente scavata nella porzione settentrionale del sito. Il sistema difensivo era composto da un ampio ingresso inquadrato da due torri bipartite ad assetto longitudinale che presenta interessanti confronti con le architetture difensive della capitale ittita datate al XVI secolo a.C.

Una serie di abitazioni sono state invece messe in luce lungo le pendici meridionali dell’insediamento, anch’esse racchiuse all’interno della cinta muraria. Si tratti di spazi piuttosto ridotti e di forma allungata adibiti soprattutto allo stoccaggio di beni domestici e provvisti di focolari singoli o doppi a forma di ferro di cavallo, i quali evidenziano la continuazione di una lunga tradizione attestata nel sito sin dal III millennio a.C.

Questa stretta combinazione di elementi esterni, legati soprattutto al patrimonio culturale dell’Anatolia centrale, e tradizioni locali evidente nell’architettura si rileva anche nella cultura materiale di questo periodo. La ceramica è infatti caratterizzata da un lato dall’introduzione, già piuttosto rilevante, di forme tipiche del mondo ittita e dall’altro dalla sopravvivenza di elementi locali visibili soprattutto nel cospicuo numero di classi ceramiche dipinte che si trovano in perfetta continuità con quelle tipiche del Bronzo Medio. -

Alla periferia dell’impero Ittita

1400–1200 (IV)Il Periodo IV di Arslantepe corrisponde al Bronzo Tardo II (1400-1200 a.C.). Anche durante questa fase l’ingresso alla collina era localizzato lungo il pendio settentrionale, anche se una nuova porta urbica venne costruita più ad ovest rispetto alla precedente (Periodo VB).

Tali riassestamenti del sistema difensivo indicano che la ristrutturazione avvenne sotto una forte influenza ittita, infatti questa fase corrisponde al periodo di massima espansione dell’impero lungo l’Eufrate, momento nel quale il sito era conosciuto con il toponimo ittita Malitya.

Anche le dimensioni della porzione di tell racchiuso dalla fortificazione tendono ad essere modificate riducendosi rispetto al periodo precedente e contrassegnando la nascita di una cittadella fortificata. La porta monumentale, conosciuta con il nome di “porta imperiale”, è un tipico ingresso a tenaglia che si ritrova in moltissimi siti centro anatolici e si collega ad un sistema difensivo che non è più un terrapieno, come nel periodo precedente, ma venne invece ricostruito in mattoni crudi allettati su fondazioni in pietra.

In quest’area è stato anche messo in luce un tunnel a “falsa volta”, scavato solo parzialmente, costruito con l’ausilio di pietre poligonali e lastre e che con ogni probabilità era profondo più di 4 metri. Si tratta di una reminiscenza della cosiddetta postierla dei centri ittiti (una galleria sotterranea che passava al di sotto della fortificazioni), anche se nel caso in questione non sembra che il tunnel passasse sotto la cinta muraria. È infatti più probabile che questo avesse un’altra funzione, ed è stato ipotizzato che si trattasse di una galleria scavata per raggiungere la falda acquifera.

La ceramica del Periodo IV è caratterizzata da cambiamenti significativi rispetto alle fasi precedenti, mostrando forti somiglianze con le produzioni dei principali siti dell’Anatolia centrale ed evidenziando ulteriormente il fatto che Arslantepe in questa momento doveva gravitare nell’orbita dell’impero ittita.

L’insediamento del Bronzo Tardo venne infine distrutto da un violento e diffuso incendio. -

L’età dei regni Neo-Ittiti

1200 – 850 (III)In seguito al crollo dell’impero ittita, una serie di piccole ed autonome entità politiche note come “regni neo-ittiti” emersero nella regione dell’Anatolia sud-orientale. Arslantepe divenne la capitale di uno di questi regni, nominata nelle fonti locali con il toponimo Malizi.

Gli scavi italiani, condotti sia in passato (anni ‘60) che negli anni più recenti in vari punti dell’area nord-orientale della collina hanno messo in luce un’ampia serie di strutture monumentali. Tra queste si segnala la presenza un grande edificio dalla forma rettangolare realizzato su di una possente piattaforma costituita da grandi blocchi di pietra sbozzati. L’edificio data al X secolo a.C. e i confronti evidenziano interessanti similitudini con alcune strutture templari levantine dell’Età del Ferro.

I livelli sottostanti, datati tra il XII e l’XI secolo a.C., erano caratterizzati dalla presenza di un imponente muro di fortificazione probabilmente connesso ad un sistema di accesso alla cittadella testimoniato dal ritrovamento di due rilievi scolpiti affini ma stilisticamente differenti a quelli rinvenuti in passato nella zona della Porta dei Leoni da Delaporte.

La produzione ceramica, e la cultura materiale in generale, continuano solamente in parte ad essere affini a quelle del Bronzo Tardo. Un nuovo repertorio di forme riflette interessanti connessioni con il mondo Levantino, segnando l’interruzione dei contatti con l´Anatolia centrale. -

Il regno Neo-Ittita di Malizi/Meliddu nell’età degli imperi

850 - 712 (II)I livelli più tardi dell’Età del Ferro sono soprattutto caratterizzati dai resti della famosa Porta dei Leoni scoperta da Louis Delaporte negli anni ’30 del secolo scorso. Questa struttura, che si presenta fiancheggiata da due lastre scolpite in altorilievo a forma di leone con testa a tutto tondo, immetteva in una corte pavimentata e decorata con una serie di bassorilievi che riproducevano scene di caccia rituale e libagione.

La Porta dei Leoni e l’intero set di bassorilievi possono essere oggi visitate insieme alla grande statua di un re rinvenuta nella porta stessa al Museo della Civiltà Anatolica di Ankara.

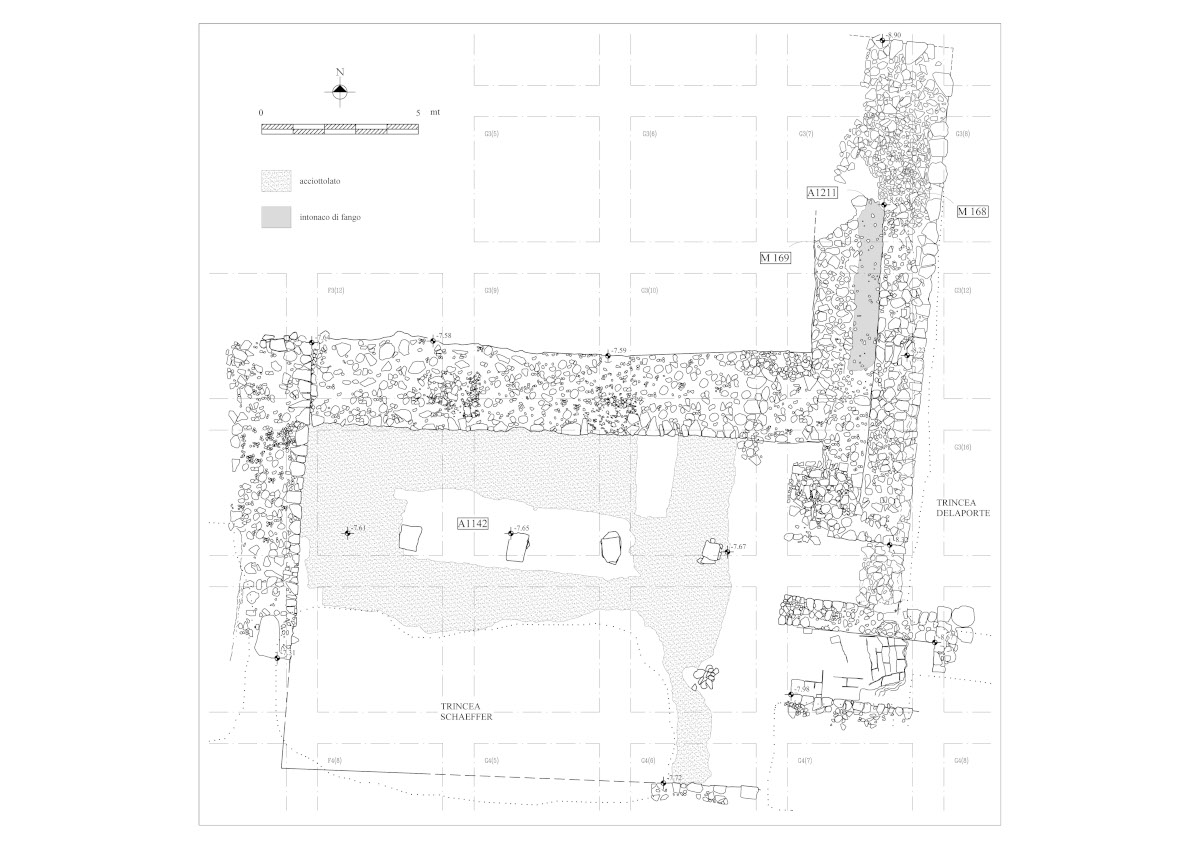

La recente ripresa degli scavi ha inoltre permesso di mettere in luce un grande edificio colonnato, datato all’VIII secolo a.C., il quale, nella sua fase conclusiva, doveva essere strutturalmente e funzionalmente connesso con la Porta dei Leoni. Caratteristica significativa dell’edificio colonnato è la presenza di una serie di pavimenti realizzati dall’alternanza di ciottoli e grandi lastre di pietra squadrata.

Il materiale proveniente dalle diverse fasi di vita dell’edificio colonnato è caratterizzato dalla presenza di classi ceramiche esotiche che permettono di collegare il sito all’interno di un network di relazioni che andava dal mondo frigio in Anatolia centrale, a quello Urarteo in Anatolia orientale, fino alla sfera di influenza delle culture Egee e Cipriote.

La conclusione del periodo neo-ittita coincide con la fine del potere e della prosperità di Arslantepe. La città venne infatti conquistata e poi distrutta dal re assiro Sargon II nel 712 a.C. e in seguito definitivamente abbandonata. -

Verso l’abbandono del sito

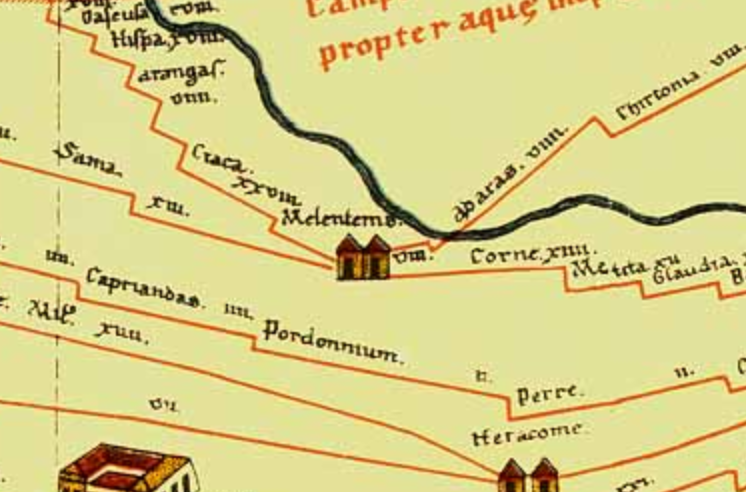

650 a.C. - 1100 d.C. (I)Dopo la conquista del regno di Malatya da parte di Sargon II, Arslantepe subisce una progressiva decadenza e il sito viene definitivamente abbandonato dopo l’invasione dei Cimmeri. Con l’arrivo dei Romani, la regione diviene luogo di stanziamento di una legione. La piana di Malatya è infatti una regione di confine dell’Impero Romano ed ospita la XII legione fulminata dall’età di Tito fino al VI secolo d.C. Il castrum romano viene costruito vicino ad un punto di attraversamento dell’ Eufrate, che viene in questo modo posto sotto il diretto controllo dall’esercito. Attorno al castrum si forma poi l’abitato di Melitene (trasformazione dell’antico nome di Melid) che si trasforma in un importante centro regionale che ricevette da Traiano lo status di municipium. A Melitene confluivano, come testimoniato dal ritrovamento di un miliario dell’età di Diocleziano, le strade militari che correvano lungo la frontiera orientale in direzione dell’Eufrate. La città di Melitene ebbe un forte sviluppo anche in età Bizantina. La sua importanza militare è inoltre testimoniata dal fatto che la città divenne la metropoli dell’Armenia Secunda.

Nelle vicinanze di Melitene, a metà strada tra questa e la moderna città di Malatya, Arslantepe si presentava in queste fasi romano-bizantine come un piccolo borgo rurale probabilmente non diverso da molti villaggi anatolici dello stesso periodo. Gli scavi italiani hanno portato in luce dei resti di un piccolo abitato di età romana nella zona nord-est del tepe e di una strada che lo attraversava, mentre di epoca più recente è una necropoli che occupa la metà meridionale della collina. Sulla base dei materiali rinvenuti (monete e ceramica), l’insediamento romano può essere datato tra il IV ed il VI secolo d.C. e rappresenta l’ultimo livello di occupazione constistente sulla collina. In epoca bizantina il sito è sede di una necropoli cristiana. Infine, nella zona nord del tepe vi sono tracce di un possibile palazzetto ottomano. A prescindere dai resti di questo ultimo edificio, in età Ottomana il sito viene sostanzialmente abbandonato a favore del centro di Eski Malatya (Melitene), più vicino alle rive dell’Eufrate.